The final section of the last level of Halo 1 sees you fleeing from the titular ring just before it erupts into fiery destruction. You jump in the driver’s seat of a warthog and frantically drive along debris filled corridors as you weave in and out of the fighting between Flood and Covenant forces. And as you do so, a clock in the corner gradually ticks down.

At first, it seems incredibly easy, even on Legendary with the reduced timer. But a wrench gets thrown in your plans when your pickup vehicle can’t get to you and you need to head to a secondary extraction point. That’s when the intensity of the mission goes way up - you engage in a desperate scramble to get to safety while the timer’s shadow looms overhead, ticking closer to zero.

In the narrative of Halo, Master Chief is a super soldier with thousands of kills to his name, and he never once dies. You might be a god capable of restarting on every errant death, but the one true timeline is one where your player character never dies and is a flawless killing machine. So when you fail to escape in time, because your warthog got awkwardly lodged in the weird alien geography, it's truly a frustrating failure.

But all it takes is a shift in perspective for that frustration to turn into something far more meditative. And that's exactly what another game, Outer Wilds, does.

Taking the middle path in the final run feels intuitive, but is often a death trap

Outer Wilds follows the path of Groundhog Day, and later Majora’s Mask, in having you repeatedly experience a time loop. You get twenty-two minutes of existence before the sun goes supernova and you get flashed back in time. The small solar system you’re in is littered with ruins and mysteries to unravel, and it's impossible to solve in a single playthrough. You’re doomed to die, hundreds of times, as you slowly put together what’s going on.

Unlike in Halo, however, your character isn’t some immortal superman who never dies. Your perception of events is exactly the same as your character’s - you’re both Bill Murray, albeit without the slow descent into insanity. You accept that dying is a necessary part of exploring and experiencing this game world. And you even begin to relish it on some level - towards the end of each supernova cycle, as the music cue sounds to signal the end of the world, I often climbed to a vantage point to watch as my universe ended in a glorious explosion.

That’s not to say I never got annoyed playing Outer Wilds. There were moments where I was minutes or seconds away from uncovering a critical piece of knowledge, before being abruptly yanked back in time. Despite all this, I was never overwhelmed with frustration - I could always try again in another loop, as I had many times before.

Witness the beautiful end to the universe as the soundtrack signals your doom

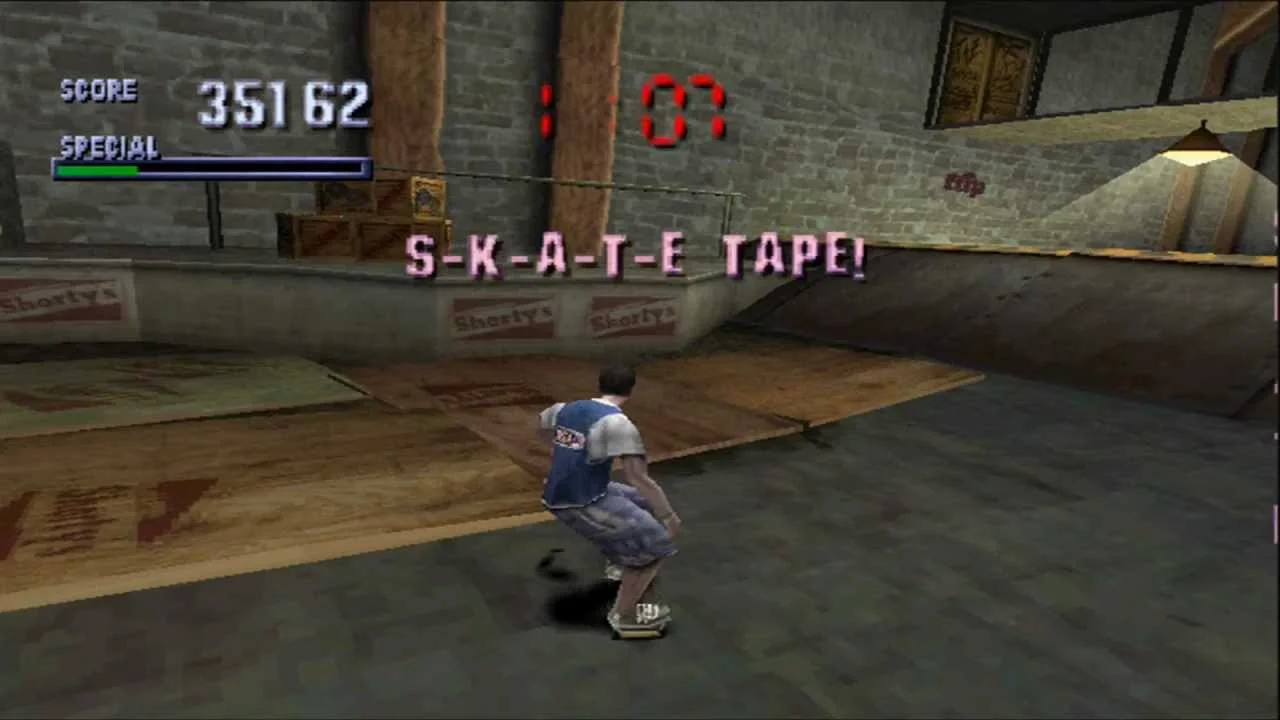

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater falls somewhere in the middle. Your character isn’t a time-looping adventurer like in Outer Wilds, but it's similarly impossible to do everything you need to in a single run. You need to explore and find secret items and locations, plan out routes between those locations and find good places to score big points. It's hard to conceive any of your early runs as failures - they’re more fact finding missions.

You’re given multiple objectives that can all be completed from your initial starting point and you’re free to pursue them in any order you wish. The measly two minutes that each round gives you is more than enough time to complete any one of those objectives, but it still throws you into this massive playground that's too hard to comprehend on your first skate around. As you slowly build your mental map of the skate-park, it does start to come together.

Once you’ve figured that out though, it does become possible to start thinking about it in similar terms to Halo. If your only goal left is to score points past a certain threshold, then that clock starts looking pretty dangerous as the minutes dwell into seconds. But the consequences of failing to hit those points feels far less punishing. For starters, we’ve already ‘failed’ so many times already by design. We’ve skated around, not hitting objectives 20 times already - what’s one more attempt really matter?

When you play Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, you achieve a particular type of Zen. Miss a jump? Turn that skateboard round and try again. Taxi hits you, driver jeering you all the while? Pick up the skateboard and try again. Miss that bloody Downhill Jam VHS Tape for the 18th time? Try, try and try again to your heart's content, improving all the while. Attempting and failing is built into the fabric of Tony Hawk’s (and Outer Wilds), so it's far less off putting when you don’t succeed.

In Halo, failing doesn’t just mean death, it literally cannot happen in the fabric of the game world. Dying isn’t just a mistake to be retried - it's a time paradox. You don’t feel the steady improvement in the same way because the narrative experience is so binary. Master Chief doesn’t have 30 attempts to defeat the Covenant, he has exactly 1. Every time you die you’re upending the plot progression of Halo down a non-canonical path.

You’re a Melon if you don’t agree with this article

But here’s the point - mechanically, these games aren’t all that different. They all require you to repeatedly try the same tasks, over and over again until you finally succeed. Their primary difference is in how they are framed, what the thematic dressing is around them. Mechanics are all well and good, but we need something more tangible to emotionally engage with.

The prescience I develop after running down a given corridor in a veteran difficulty COD campaign is no different from memorising the location of all 5 SKATE letters on a given Tony Hawk’s level. We learn from our experiences and improve in both of these games, but how punishing it feels to ‘fail’ is completely different. Dying in a single player FPS feels like the end of the world (and often is), whereas running out of time in Tony Hawk’s feels like you’re playing the game exactly as it was intended. But they’re one and the same if you’re willing to take a step back and shift your mindset. If I had learned this lesson earlier I would have had a much easier time with a game like Dark Souls.

One of the (many) things that Dark Souls accomplished was in flipping the terms of death and failure. Not only is there an in world explanation for your repeated deaths, the whole philosophy of the game is to die and learn by dying. The world is dark and full of terrors and you are punished brutally by losing experience on death, but that's not the true foe. Going on tilt, throwing your controller in frustration and getting angry are your enemy. Once you accept that each new challenge will basically require you to die 20 times, you can learn to overcome it. Defeating Dark Souls isn’t about not dying, it's about fully accepting that you will die many, many times in pursuit of victory.

So, next time a game puts you on a clock and you start tilting, take a moment to reflect on what the actual stakes are. You may find that they’re far less dramatic that you had originally thought, and that death isn’t always the end. If playing Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater has taught me anything, its that focusing on moment-to-moment improvement instead of ‘winning’ will lead not only to better results, but a more enjoyable experience overall.

You can listen to our podcast on Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater here.