There was a certain narrowness to my experiences playing video games as a child. I didn’t own a console, handheld or otherwise, so I only ever played the PC games that my Dad had bought for his own enjoyment. Effectively, this meant that I played a lot of Duke Nukem 3D and Red Alert, and not much else.

Eventually I got a PS2, and my horizons broadened slightly. Looking back on my first play-through of Metal Gear Solid 3 makes me wince - I killed every single enemy soldier with a gun, barely comprehending the stealth mechanics. I got my own PC and played Deux Ex, and had my mind blown to pieces by its RPG systems. I very gradually expanded out of the FPS and RTS rut I dwelled in, but only got so far.

One of the main reasons I started my podcast a year ago was to go back and patch the holes in my knowledge of video game history. In the same way that some very old movies are still worth watching, I was confident that there must be some classic games of the past still worth playing. Over the past year I’ve played more than 30 video games that are at least 15 years old. I like to think I learned some lessons along the way.

It wasn’t very long into the podcast before my limited experiences started to catch up with me. The show structure is such that we alternate who gets to pick the game to play for that fortnight’s show. And for episode 6, my co-host, James selected the highly renowned racing game F-Zero GX. At the time, the only racing game I’d ever played in my entire life was Need For Speed Underground 2, which unfortunately barely counts.

In F-Zero GX your vehicle is insanely quick and you are heavily incentivised to go far faster than you can actually handle. There are boost pads strategically placed right before areas with no rail guards and hairpin turns, daring you to tempt fate. The health of your racer is even tied to your boost gauge - the game is an elaborate dance of risk and reward as you push yourself to the absolute limit.

And I hit my limit almost immediately. Mission 3 (3!) of the single player campaign is when I threw my hands up in frustration and declared the game stupid after attempting to beat it for a solid hour. The level of perfection demanded seemed utterly ridiculous so early into the story. As a complete newcomer to the genre I felt intimidated by just how hard the game was. If I didn’t have a podcast episode to complete, I would have given up there and then.

Instead, I persevered. I decided to grind out the Grands Prix, repeating them over and over again until I finally emerged victorious, first on easy, and then on normal. My hours spent zipping around the neon-lit tracks eventually paid off, as I returned to mission 3 and finally defeated it after another hour of poorly timed turns.

There is something very rewarding in being utterly terrible at a game and having to learn how to play it. I had a tendency to play modern games that I was intrinsically skilled at, selecting them on the hardest difficulty and breezing through. I had viewed games as a way of flexing my mastery over the medium. F Zero GX showed me the joy of gradually improving your abilities, moving from a complete newbie to someone halfway competent. And later on in the year, when I encountered similar challenges in Vagrant Story and Heroes of Might and Magic 3, I felt better prepared to rise to the challenge.

To some degree, you’ve got to do it alone. If you google any game made in the past 10 years, you’ll get a thousand youtube videos, a hundred guides and ten wikis, all of which meticulously detail every item, monster and piece of lore that pertains to that game’s world. But the same cannot be said of a lot of older games, where GameFAQs becomes your premier resource, ASCII diagrams and all.

There was a point playing Megaman Battle Network 3 where I felt hopelessly lost. The game is a very weird mix of genres, combining Pokemon, rhythmic dodging and deck building into a remarkably cohesive whole. I was fighting a boss called Bubbleman, who’s attacks were super effective against my fire suit (that at the time I didn’t know you could remove). True to his cowardly personality, he spent most of the fight well protected under various pieces of cover.

The problem is, I couldn’t just look up a walkthrough for the answer - although I definitely tried to. My specific circumstances didn’t really line up with what the guide was advocating. There was an element of just having to improve like in F-Zero, but what I really needed was a different strategic approach. And so I experimented.

I tried out all the weird utility chipsets at my disposal. There was a move that summoned a rock, and another that pushed any entity forwards. There was a mechanical timed bomb attack that went in a straight line, before honing in on an enemy as it became adjacent to it. There was even a move that pierced all enemies in a row, including those damn bubbles that kept providing layers of protection.

Part of the brilliance of Battle Network’s gameplay is that it gives you all the tools you need to overcome your problems. If you’re struggling with your default approach, you can simply switch up your deck configuration and crush that one problematic opponent. It feels amazing to figure this out by yourself, giving you a real sense of ownership over your victories.

Now when I’m faced with road blocks in games, both modern and old, I try my hardest to not consult outside help. I had to learn to do without outside resources while playing Battle Network, and got a lot of value from playing around with the systems available to me. It's not always obvious, but there’s almost always a way to solve your difficulties if you look hard enough and tackle things with a little imagination. It even helped me get past the seemingly impossible missions of Tribes: Vengeance (on hard), although ‘cheese’ is probably a better word for the approach I took.

Not all games put gameplay front and centre. The moment to moment gameplay of video games is something I always harped on about as being the most important thing. I was very blasé about music, sound and graphics. James, expressed actual shock when I said I didn’t listen to the music in Banjo Kazooie because I found it annoying and immersion breaking.

Over the past year, my view has changed. The aesthetics of a game are far more important to me than they used to be. I’ve been exposed to many different musical and graphical styles and feel more comfortable discussing which ones I like and dislike, rather than sweeping them all under the same generic banner.

With graphics, I learned that any attempt to ape realism is doomed to suffer the test of time. Max Payne, for all its brilliant quips and well realised noir storyline, is as grotesque as the world it paints. Armored Core is even worse, an endless succession of identical construction sites and tunnels, portraying a dystopian future only in shades of grey and brown.

Conversely, the far more stylised cell shaded graphics of Viewtiful Joe, or the deep violet shadowy scenes in Policenauts are not only beautiful, but will continue to look so for years to come. Games like Crysis now look quaint, and eventually even Uncharted 4 will seem like a shadow of what it once was. There is a more intrinsic beauty to these games that commit to a more abstract art style.

The music of these games is something that took me far longer to fully wrap my head around. Eventually though, I discovered that the most important thing to me is the music’s emotional resonance. The soundtracks that stand out the most are the ones where the music moves in harmony with the atmosphere.

Games like Archimedean Dynasty (soundtrack) and Red Alert 2 (soundtrack) have fine OSTs - but their tracks tend to blend together into industrial techno noise. And it's very hard for me to tie those tracks with specific moments in those games I experienced; there are no story beats connected to a moment of betrayal or despair.

Then, you have masterpieces like Cave Story’s soundtrack (remastered!). Over the course of the game you have joyous exploration, intense battles, eery solitude, melancholic reflection and triumphant cooperation. Castlevania: Symphony of the Night assigns different pieces of music to different sections of the castle, making returning to areas with new abilities rewarding in more ways than one. If you’ve played the Halo campaign enough times, you can listen to this with your eyes closed and know exactly what part of each level you’re up to.

The music from these games are absolutely essential to their identities. My lack of appreciation for the music in games wasn’t a mere preference for gameplay, it was an ugly blindspot. I’m not saying that tight hitboxes or smooth controls shouldn’t be praised. But it's listening to these soundtracks that make me remember how I felt as I experienced these games, and it's that emotional connection that elevates them above mere technical pieces. I have these old games to thank for awakening me to the vital role that aesthetics play in video games.

Yet for all my general positivity about classic games, these games tend to suffer from two huge issues: their controls and user interfaces. When you sit down in front of pretty much any modern game, you immediately know how to control the game and your character. Your fingers curl up in front of ‘WASD’, you press the trigger buttons to swing your sword and you rotate the camera’s perspective with the right stick. It was not always this simple and intuitive back in the dark ages of the 1990s.

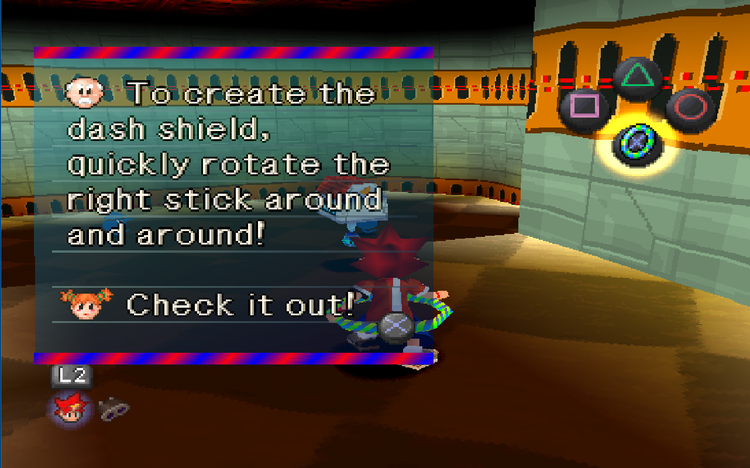

Ape Escape was the pioneering game of analog controls for the PS1, and it really shows just how little developers knew about these kinds of control schemes. The camera was controlled with L1 and R1, while the right analog stick swung your weapon or used your other gadgets. It's all very strange, and descends into pure frustration when you’re chasing monkeys around in circles, rotating the stick to power up your hula hoop dash while you collide into scenery. And while that bizzare control scheme is now an intrinsic part of the gameplay experience for fans, it just made me lament how much more fun I’d have if the game didn’t require me to make weird hand movements to control my character.

Even worse to control is Armored Core, from the creator of Dark Souls, From Software. The game is built as an arcade-like mech brawler. Enemies are fast and agile, everyone has jetpacks, and you have to constantly be on the move, dodging and returning fire . This premise sounds amazing, until you actually get behind the controls of the mech, and realise that this game came out before analog sticks existed.

You awkwardly clank and screech into position, barely able to track enemies, repeatedly strafing into walls. If you get too close to an enemy you literally cannot turn to keep up with them, so you need to reverse like an 18 tonne truck to re-assume a mid range engagement length. It's not that this clunkiness is inherently bad, it's just the pace of the gameplay demands more responsive controls. Archimedean Dynasty, on the other hand, hit the right balance, because it felt more like you were at the helm of a cockpit, flipping switches and pressing buttons.

And I would be remiss not to mention the many other suspicious user interfaces I had to deal with. Vagrant Story is a game I definitely have mixed feelings about. I strongly disliked its gameplay, even as I simultaneously praised its wonderful story telling. But without doubt, the worst aspect of Vagrant Story is its atrocious user interface.

In many ways the primary gameplay of Vagrant Story is in the many menus you have to deal with. The game bombards you with an endless stream of overlapping systems - gems, styles, resistances, risk, types, chains, break arts - and has no intention of clearly explaining how they all interact. It feels like 70% of your time playing this game is flicking through menus, comparing and contrasting every stat that exists while not understanding a thing.

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night requires you to sort through several menus to find a health item, equip it, then throw it at your feet before you can finally eat it. And then you need to go back into those menus to re-equip the item you need. I would forget how to transfer items between my characters in The Lost Vikings every single time I booted up the game, a far departure from Blizzard’s usual level of polish

It's not that complexity is in and of itself a bad thing - it's that there is no economy of information provided. There are layers and layers of obfuscation between you and what you’re trying to accomplish. If these games ever get a remake, the number one thing they need is not a streamlining of they’re intrinsic mechanics, but instead a complete reshaping on how these things are presented to the player.

Today, there is a standardisation across control schemes, and a refinement of most UIs that I am incredibly grateful for. We have moved on from the wild west of crazy and diverse control schemes, and it's definitely for the better.

The final thing I learned and my biggest takeaway from all of this is something that I’ve been struggling to articulate for weeks. I’m a very critical person by nature, wanting to pick apart every piece of media I consume to better understand it in terms of strengths and flaws. I want to definitively ascribe a game to its proper designation as a masterpiece or miserable failure, neatly stored away in compartmentalised opinions.

Over the past year, however, I noticed something strange about my perception of the games that we played. The way I remembered feeling while playing the game was often very different from how I felt whilst reflecting on the experience. I remember disliking Thief’s third mission, Down in the Bonehoard, because instead of stealthily evading human guards, you were instead faced with braindead monsters. But I now think of that mission almost fondly, robbing tombs, evading traps and trying to navigate the twists and turns of its labyrinthian level design. So the question then becomes, how can I possibly reconcile these two experiences? How can I both hate and love a game, or even a specific section of a game, at exactly the same time?

The truth is, games are a heavily contextual medium. Taking a small slice out of a game and trying to render judgement is like trying to understand Memento based on the middle 20 minutes. It's very hard to comprehend in the moment what a game is trying to accomplish, particularly when it's deliberately cultivating a limited feeling of frustration. Overcoming a challenge set up for you is incredibly gratifying - and the frustration of failure is an essential part in creating the jubilance of victory.

This even extends to games I actively disliked and did not recommend. Silent Hill 2’s story is masterful, but it's gameplay is a repetitive grind of stunlocking enemies and item hunting. At the time, I thought that if the gameplay was more like a telltale adventure game that the experience would be greatly improved. If you were to remove the feeling of being James Sunderland, however, you would lose a great deal of atmosphere in feeling trapped in the grimy and disturbed town. What I view as poor gameplay is still an important part of the overall experience. Ultimately, I’m glad that I did actually play the game from start to finish, regardless of my feelings at the time.

This is all to say that the way I view criticism of video games has fundamentally changed. The point isn’t to neatly dissect games, and sort them into boxes labelled good or bad, but instead to start a discussion that's reflective of your personal opinions. One of the strengths of our show is that James and I have very different tastes in video games, which often gives us completely different perspectives on what a game accomplishes. And what we provide our listeners is not judgement from up on high, but more a platform of ideas for them to engage with and share their own, whether it's futilely shouting at us in their car on the way to work, or more directly on our discord server.

From the very beginning, what we wanted was to argue about video games. Turns out that not only did we argue with one another, but also at length with our listeners and even our own selves.

Your time is a precious commodity. There are endless tv shows to watch on netflix, new games to play, friends to see and hobbies to consume. It makes it difficult to argue that you should putter around in games more than 15 years old. Amongst the garbage that's strewn throughout history though, some of these classic games are absolutely worth your time to play today.

It was a wilder time back then. The games are a little messier, more confusing and don’t shine with the polish that you would expect from a game produced today. But the best of them still offer a unique angle, and a worthwhile experience, if you’re only willing to give them a chance.

You can listen to Retro Spectives directly on our website, on Spotify or Itunes, or anywhere else you normally listen to Podcasts! Join the discussion on our discord server, and let us know what game we should play next!